Peeping Tom, by invitation

Archived from May 11, 2023:

It’s funny how much you can learn about yourself by doing something for other people. I have no illusions about my political leanings, nor do I make any attempt to conceal them. I operate from the view that all participation in society is political, whether we want it to be or not, and so it is better to be aware of what you think about the society you live in. Even someone asserting that they “aren’t political” is, in and of itself, political. Yet, writing these weekly musings has forced a certain amount of coherence, and revealed a through-line of community I don’t think I realised I used as a framework so frequently. Trying to care about the world is complicated. If, for example, you become very invested in food insecurity and begin looking for ways to alleviate it, it won’t take very long to realise how intimately tied to housing access, labour rights, red lining and racism, food access is. To care about one thing quickly leads to the overwhelming situation of realising you're condemning yourself to care about everything. Counterintuitively, caring about everything, housing, education, healthcare, everything you can imagine, can quite succinctly be expressed as caring about community. Though this certainly doesn’t make it take any less energy to go about trying to understand the failures of systems, nor streamline attempts to improve them, it does insinuate the heartening reality that even the simplest kindness is a radical and community building act.

The bad news comes back to the fact that a community requires effort from the majority of the group to find stability. There are two ways that this effort manifests: a community oriented, outward effort or a private property driven, hyper individualist effort. Unsurprisingly, I’d like to talk about the latter. The idea of the panopticon has existed for a long time; it was originally conceived of by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. It describes a prison built around a single guard tower, the theory going that if all cells face the all seeing guard, prisoners will behave better; not because they are being watched, but because there is always the potential being watched. Needless to say, this is a hyper-utilitarian view of people and incarceration. We’ll have to get back to the inhumane treatment of incarcerated people at a later date. Rather, let’s talk about Bentham proposing this theory as useful in all facets of society to impose order through surveillance. His belief was that with the threat of constant surveillance, morality would be improved, health, economy, everything would be better. Except, perhaps, happiness. What Bentham proposes may seem, at a surface level, useful, but it takes only a few questions before the holes in the logic become apparent. The structure of the panopticon should immediately beg the question of who is doing the surveilling and what benefits they would gain from the subjugation, especially when you take the notion to society at large. How does one gain the power to observe? Do we know that they’re trustworthy? What measures will be taken to assure the power to view isn’t abused? If it is, will there be repercussions or are those who observe only held to account by their own standards, given that they are the ultimate authority? The most famous challenge presented against Bentham’s panopticon was Michel Foucault, who wrote extensively about surveillance in Discipline and Punish. For anyone familiar with Foucault, it will come as no surprise that he was appalled by the proposition of mass dehumanization.

“He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication.”

Here, he quickly and concisely explains the implications of being in a constant state of observation, though not only for the prisoner; he also alludes to the world view of the guard. A person who sees no humanity in a human, who sees only data trapped in flesh, the object of punishment, observation and duress. The world Bentham envisioned necessitates a hierarchy and a vast disparity in power, and while he was not a particularly self reflexive writer, it doesn’t feel like a far leap to assume a well off Englishman in the 18th century would believe that it was those exactly like him who would be worthy of the power in this arrangement. Now, historically, old white British men can hardly be trusted, so it would behoove one to be critical of any structure that immediately assumes the morality of a group with a lacklustre track record. This also, of course, implies mass censorship based on the standards of the authoritative group, something that a cursory look at history will reveal quickly leads to very extreme measures of enforcement. It will surprise no reader that I agree with Foucault. While the system may see some shallow benefits of a manufactured “peace”, if it comes at the price of the peace and safety of individuals, it is likely not a peace worth having. Perpetual surveillance and constant threat of punishment dehumanizes, abuses and reduces our ability to live fulfilling, fruitful lives. It, as so many systems do, benefits naught but a few. Unfortunately, we live in something quite akin to a large scale panopticon.

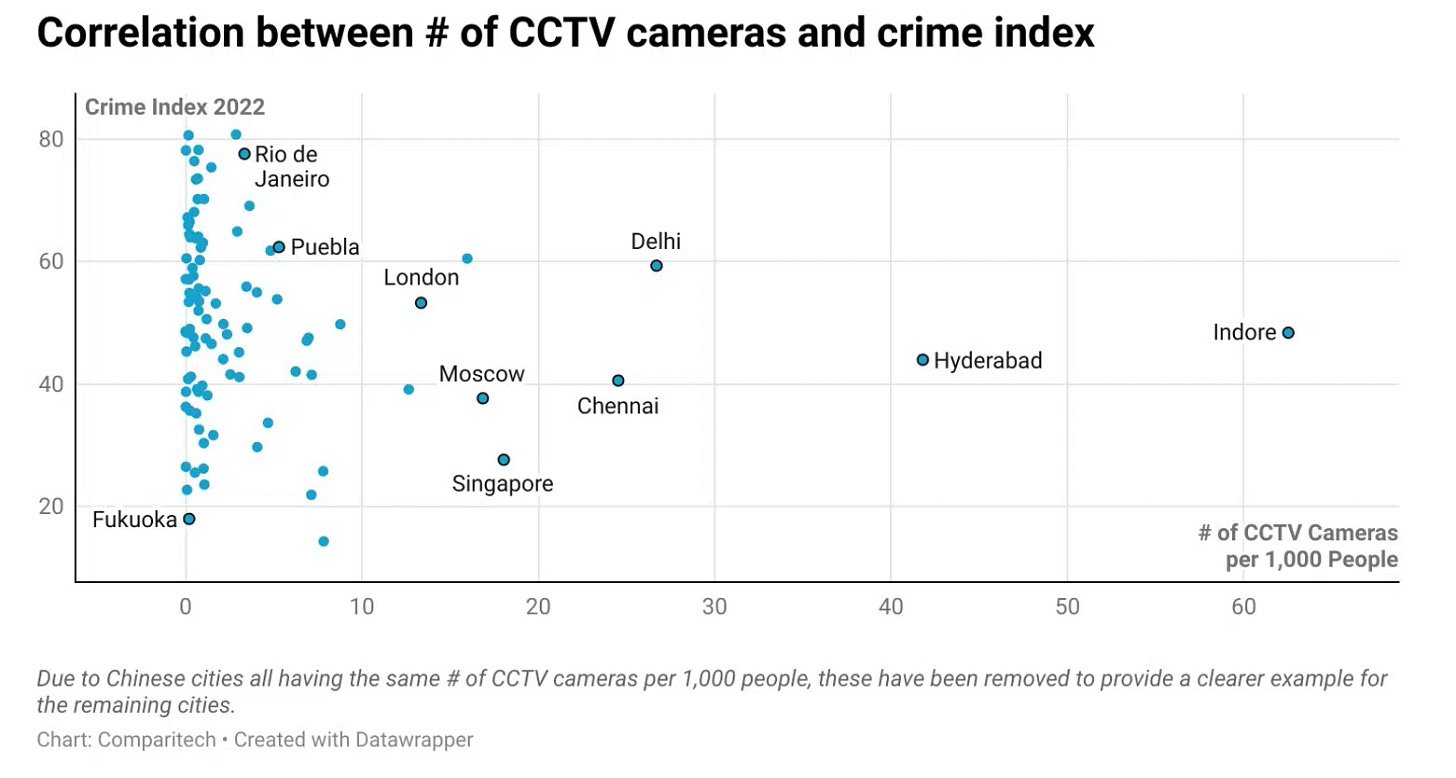

Surveillance has increased exponentially as cameras became cheaper to produce and networks easier to maintain. A single data point to illustrate: Shenzhen, reported that there were 1,34 million cameras in 2017 with 16,68 million planned. While an extraordinary amount of cameras are concentrated in China (an estimated 54% of the 1 billion cameras, globally), the trend of surveillance is on the rise globally. Urban centres like London (127,373 cameras for 9,540,576 people = 13.35 cameras per 1,000 people), Delhi (436,600 cameras for 16,349,831 people = 26.7 cameras per 1,000 people), and Los Angeles (34,959 cameras for 3,985,520 people = 8.77 cameras per 1,000 people) are all included in the top 10 most surveilled cities in the world. To illustrate part of the rhyme and reason behind this distribution:

The only U.S. city on the list is Los Angeles, which contains some of the country’s wealthiest neighborhoods and municipalities. That includes Beverly Hills, which according to the Los Angeles Times, has over 2,000 cameras for its population of 32,500. That translates to about 62 cameras per 1,000 people, meaning that Beverly Hills would finish at #2 in the global ranking if it were listed as a separate entity.

Most, if not all, of this surveillance has expanded based on an obsession with private property, the extension of which is assumed to be personal safety. As communities are increasingly privatized (remember the death of the third place?), from corner to absolute corner, the obsession with surveillance only grows. A smaller and smaller group of people own more and more and will use all their means to ensure that everyone else knows they are not welcome. A community pared down to only their wealth and the brim of their own hat. All of this need to “protect” might have you believe that crime is at an all time high; people desperate to keep themselves safe, to protect their homes, but in reality it’s just a trick played, willingly or not, by news organizations that understand violent stories get viewers. The logic goes: it’s good to know when bad things are happening, and it’s even better to know that they are not happening to you. Now, one thing I have failed to mention about all the statistics I cited is that these almost exclusively reflect publicly installed surveillance. While there is some wiggle room in the data, it’s hard to pin these numbers down exactly given the 1 billion total global cameras, it is harrowing to think that these numbers are the easier ones to track. This is where Ring comes in.

Ring is the Amazon owned, video enabled doorbell that has slowly crept into communities across North America. The insidious thing (or rather one of the insidious things) about Ring is that the people who install them may feel that they are creating a closed network of surveillance on their own property, but in reality they are feeding a vast network whose stewardship is fully out their control. A couple weeks ago I wrote about a slew of civilian on civilian shootings that occurred in the states; I wrote about the paranoia and isolation required to become the kind of person who shoots someone for pulling into the wrong driveway. I would argue that Ring cameras are a physical, documented, panopticon manifestation of the same sentiments. The need to “protect”, to “watch”, to call the cops on someone you don’t recognise. Ring is not considered a public installation, rather a private installation, the same way a CCTV camera in a bar would not be counted in the aforementioned statistics. Though, unlike a bar, Ring cameras observe public spaces; they observe and document people who are walking their dogs, doing groceries or just out visiting friends. They are on private property, but they survey public property.

Ring is effectively building the largest corporate-owned, civilian-installed surveillance network that the US has ever seen. An estimated 400,000 Ring devices were sold in December 2019 alone, and that was before the across-the-board boom in online retail sales during the pandemic. Amazon is cagey about how many Ring cameras are active at any one point in time, but estimates drawn from Amazon’s sales data place yearly sales in the hundreds of millions.

Don’t you love the idea of a company in control of millions of cameras being cagey about their data? Why read dystopian literature when you can just live it. I understand that the vast majority of people who install these have, what they believe to be, good intentions, but I also believe that is deeply naive in a way that is virtually inexcusable. I know that I cannot expect everyone to be as plugged into the nightmare matrix as I am, but we live in a time where it would take more energy to believe that Jeff Bezos is worth trusting than not. The impulse to protect “you and yours” is the exact sentiment that leads to installing a camera with no regard for where the footage goes, that leads to isolation, that leads to paranoia, that leads to violence. It’s not to say it will happen to everyone, every time, but it is hard to not see a trend. I also find the whole thing exhausting because it should be extremely obvious that a camera that monitors the sidewalk in front of your house is not going to stop crime. It’s more than likely just going to cause more harm. Imagine creating an entire app based on monitoring and then being surprised when the users are extremely racist. I couldn’t write a worse SNL skit if I tried.

If, for once, the data is to be believed, what stops crime doesn’t stop it, so much as prevents it. Food access, education, healthcare, reliable public transportation, housing. All of these things contribute to a culture of safety and security that benefits all its citizens. In turn, it also eats away at cultural myths of morality being associated to wealth, of value being assigned to material output, of all the stories of danger we are told. The easy route is to fear others, to believe that you are the sole saint among men, but this fear is the root of so much violence we live with. A camera facing your porch is not going to solve housing access, food access, wage inequality, violence or any other of the myriad of problems that plague our world. Not to be a broken record, but the things that will help those are building your community from the ground up. It is going to come from knowing that with security for others comes security for yourself, that trust and comfort come from conversation and familiarity. It comes from falling in love with the world around you all over again.

Despite the news, I still believe we can work to a more just, integrated and equitable world. There is room and access for everyone, the only thing standing in our way is the systems that tell us there isn’t a better way. Don’t trust Jeff Bezos to tell you what is going to make you safer, happier, more fulfilled from his 500 million dollar yacht. A person so deluded to think that something that like will be the thing that finally fills the void is not a person to take seriously, I do not care what his valuation is. At no point in history has wealth been a good indicator of morality. As a matter of fact, I would venture to say the inverse is true; all the more reason to look into your own community to find value, compassion and care. We are all much closer to one another than the most powerful want us to believe. So go forth, friends. Talk to your bartender, ask your grocer how they are, leave small footprints of kindness everywhere you go. To be kind is to be political, is to be radical in a time that tells us to fear one another. And I, for one, believe in us.

Mandatory picture of my editor:

As ever, thank you for being here, friends. All the support and kind words are immensely appreciated. Comments and suggestions are always welcome and feel free to share if you think you’d know someone who might enjoy the noise.