Hyperfixation

Archived from Apr 13, 2023:

And I feel sure that my wounds will healAnd I will bloom here in my room

With a little water and a little bit of sunlight

And a little bit of tender mercy

- The Mountain Goats, Absolute Lithops Effect

I am, I think foundationally, a bit on the intense side of things. I feel intensely, and I fixate on things. More than once, friends have told me maybe I should tone it down. I have a tendency to chase down the dark, the grim, the immediate world and stories that reflect it, magnify it. I know they say it out of concern, and that makes it even harder to explain how much it feels unavoidable, that it is part of me. I understand why people enjoy lighthearted books, movies and stories, but I rarely seek them out for myself. I suppose, in a certain way, it’s cathartic. It’s seeking stories and patterns in history and the world, rummaging for scraps of hope and the good fight being fought. I understand why most people wouldn’t like my reading list, but it has created, over many years, the framework I live and think in. Maybe it’s intrinsic, maybe it’s habit, but that’s only part of what I want to talk about. I’ve been thinking a lot about hyperobjects, the notion, the book and the things that could be called hyperobjects. I think this concept wraps up and around my feelings of despair and hope, the estranged cousins I find so deeply entwined together throughout stories and history.

A brief(ish) overview of the concept: Timothy Morton, professor and modern philosopher, says in interviews that the book, “Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World”, fell out of them over the course of 4 days. It’s a heady and academic book. I think I would struggle to suggest the whole thing to anyone who isn’t explicitly interested in philosophy but I find the overall concept useful. In essence, Morton uses the term hyperobject to describe something that is “massively distributed in time and space relative to humans”. In the book, they frequently speak of climate change as a hyperobject; something intangible that has undeniable consequences on a massive scale that spans decades. A concept patched together across events and changes, frequently impossible to see the end of. Hyperobjects, as a framework, is a useful tool for approaching these things that generally feel as though they are outside human comprehension. It can be very overwhelming to navigate through the news and events of such a deeply interconnected world, and thinkers like Morton can help make sense of things.

Personally, I find the notion of hyperobjects takes a bit of the pressure off. These things are massive, and basically beyond comprehension, so why spend time trying? That’s not to say it’s not worth pursuing change and betterment; in interviews, Morton has been confronted with the pessimism that is easy to find in their book. It seems, over the years, they have come to regret some of the examples and tone of the book, going so far as to say they wouldn’t write it again, or at least not the same way they had. Hyperobjects may be beyond what we can meaningfully interact with, but our lives, our communities, our actions are not. “How dare I patronize people who are suffering?” Morton says. The dichotomy of such a cerebral approach and their clear empathy for the world around them is part of what I think makes Morton such an interesting thinker.

I find this contrast, found in Morton’s interviews and their writing incredibly human. I also find it very easy to relate to. I spend a lot of my time having to remind myself that other people don’t feel the same way as me. They may feel less, or at least less intensely, or simply do not have the threshold for the grimmer things in life that I do. While it is by no means a cure all, I find the idea of hyperobjects helps regulate the intensity and immensity that I sometimes experience the world in. It allows me to name not only the thing, but the feeling, which may or may not have been Morton’s intention. To confront something as large as the systems that dictate so much of our lives, or to think about the fact that all the concrete in the world almost outweighs living matter on the planet, or climate change, is a feeling all its’ own. While Morton never asserts that hyperobjects are purely negative, it is easy to fall into that line of thought. I think this is in part because we feel little need to intellectualize the wonder we so frequently feel at the natural world. While the Amazon biome could be considered a hyperobject in time, size and scope, I think people would be less inclined to categorize it as so, lest we dampen the beauty of something so grand. When I do think of the examples Morton gives, in all their negative connotations, I can’t help but think of H. P. Lovecraft and the madness that befalls men when gazing upon the Old Ones. When I feel on the brink, stuck in my own head, Morton’s writing becomes a small talisman, grounding me in sanity and an ability to move through and past the incomprehensible.

I find it hard to look away from the world, and this is a blessing and a curse. I frequently find myself envious of those who aren’t regularly all consumed with the absurdity of our modern world. It sounds blissful in a way that feels completely out of reach for me. And yet, the intensity I live with is what allows me to operate within the theoretical opposite of hyperobjects. I do really believe that life is about the little things. While not a hyperobject by definition, my life is similarly built up by moments that create a whole. It is built of decadent meals, sunshine in the morning, bursts of laughter, voice notes telling me I’m loved, my cat’s small chirps. It is in spring time, and longer days and putting pieces of myself back into place after a long winter. It is woven together through action and love and memory in a way that no individual sentiment could total on its’ own. I do focus on the dark, the absurd, the strange and often, the upsetting, but it’s this focus that allows me to turn to joy so intensely. I vacillate, and maybe a more stable existence would be easier, but it breaks my heart to think of my joy being dampened, having spent so long looking for it. Thinkers like Morton help me appreciate the ferocity that tinges all my experiences, they serve as a reminder that to live deeply is a gift. To live so deep is to know that when the immensity feels like it might drown you, there will always be a hand to pull you back to the surface.

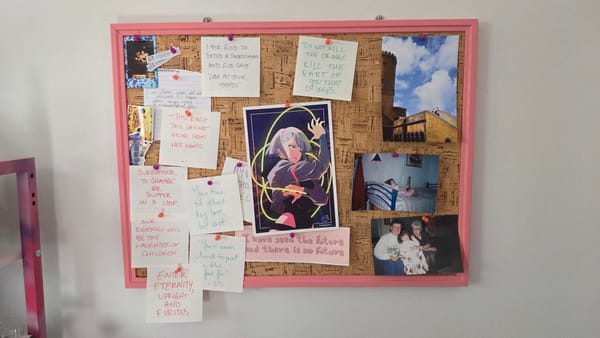

Bonus blooms from spring: